Research Interests

The Neuroscience of Cancer

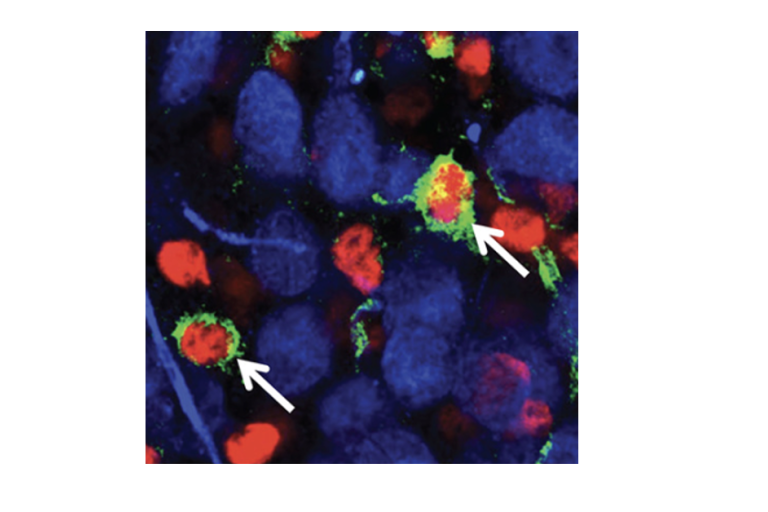

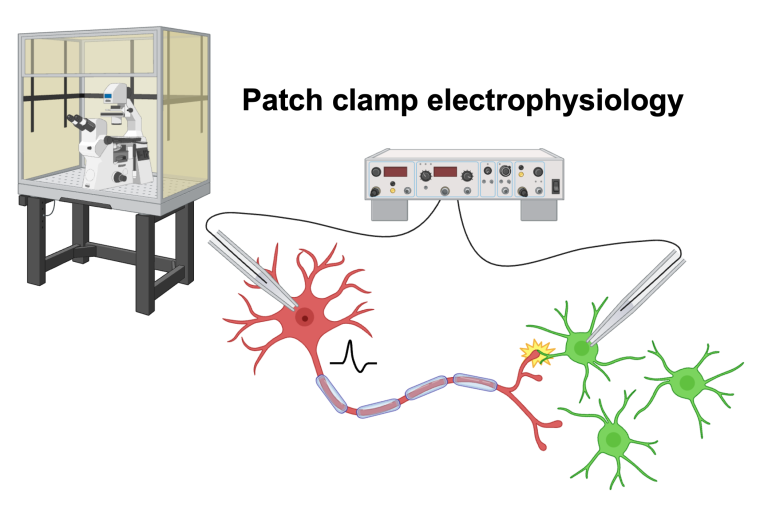

Gliomas dynamically respond to neuronal activity, which can impact tumor progression, but the mechanisms by which this occurs vary between glioma subtypes. This heterogeneity suggests that potential therapeutic targets that are clinically relevant for one subtype may not be relevant for another, highlighting the importance of studying gliomas as related but distinct diseases. Gliomas with isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutations are the most common malignant primary brain tumors in young adults, making up 70-80% of low-grade glioma and secondary glioma cases. While these tumors are often initially slow-growing, remission is rare and malignant transformation to a higher grade is common. Despite the prevalence of this devastating disease, little work has been done on the interactions between IDH mutant glioma cells and neurons in their microenvironment. Other glioma subtypes have been shown to receive synaptic input from neurons (Barron et al., 2025), reminiscent of the neuron-glial synapses formed between neurons and normal oligodendrocyte precursor cells, the putative cell of origin for IDH mutant gliomas. The Barron lab aims to determine the effect of neuronal activity on IDH mutant glioma growth via synaptic and non-synaptic mechanisms.

IDH mutant gliomas are typically slow-growing, and while patients may survive for many years, they often experience severe neurological symptoms, including seizures, memory loss, cognitive decline, speech difficulties, and motor deficits. A major knowledge gap is how these tumors disrupt neuronal function at the cellular and circuit level within the brain's microenvironment, contributing to these debilitating symptoms. Gliomas are known to alter local neuronal activity, creating seizure-prone states through hyperexcitability. This is particularly relevant in IDH mutant gliomas, which are associated with a higher clinical incidence of seizures. The underlying mechanism is believed to involve 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG), an oncometabolite produced by mutant IDH. However, recent clinical trials show that even patients treated with the IDH inhibitor vorasidenib, which reduces 2-HG levels, continue to experience seizures. This suggests that some mechanisms driving hyperexcitability in IDH mutant glioma are independent of 2-HG and remain poorly understood. The Barron lab is interested in deciphering the biological basis for these symptoms related to cellular and circuit-level changes to neurons in the glioma microenvironment.

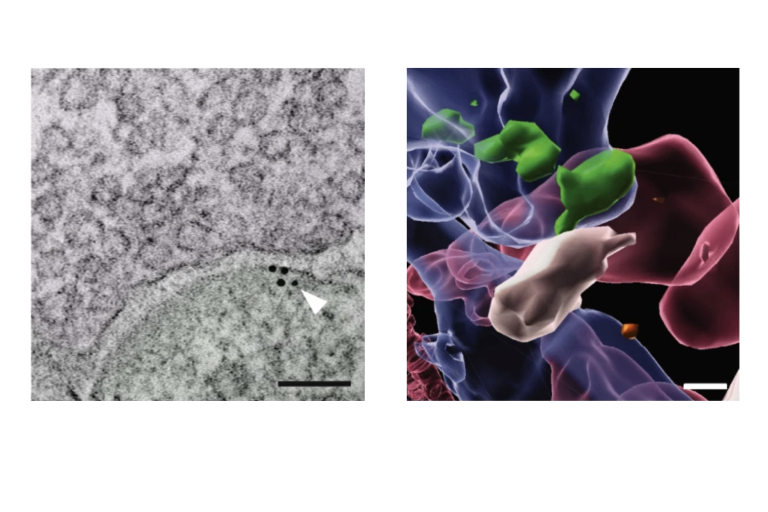

Cancer tends to recapitulate mechanisms of development. The electrical activity of the nervous system is a powerful regulator of neurodevelopment and plasticity. OPCs are self-renewing glial cells in the central nervous system that persist into adulthood and differentiate to become myelinating oligodendrocytes. These enigmatic cells are the only glial cell type in the brain known to take synaptic input from neurons, but our understanding of the effects of neuron-glial synaptic transmission is incomplete. These neuron-to-OPC synapses elicit a Ca2+ response and spiking in a subset of OPCs, but the mechanisms by which these responses may lead to changes in neuronal activity and circuit remodeling are not fully elucidated. A focus of the Barron lab is exploring the role of neuron-to-OPC synapses in the healthy brain, particularly mechanisms of Ca2+ signaling in postsynaptic OPCs leading to adaptive myelination and how electrically active OPCs regulate neuronal activity.