Our Mission:

Individuals diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), dementia, and diverse forms of psychosis, including schizophrenia (ScZ), frequently experience severe memory impairments. Significantly, these conditions often correspond with discernible damage to a crucial brain region: the hippocampal-entorhinal cortex (HPC-EC). Even though these disorders are widespread and have profound impacts, our understanding of how memories are specifically formed, accessed, and retrieved at a systems level is still in its early stages. It's crucial to understand that disruptions in memory formation and retrieval aren't mere neural anomalies; they profoundly affect an individual's daily life.

Addressing this knowledge gap, our cutting-edge research team is dedicated to decoding the complex neural dynamics involved. We are especially interested in the moments of successful memory access and recall during episodic working memory tasks. Our primary goal is to illuminate and decode the intricate interactions within the crucial hippocampal-cortical network. Through such investigations, we aim to lay the groundwork for more effective treatments and a richer understanding of the memory system.

Our current research projects encompass:

1. Conducting in vivo super-large-scale recordings in HPC-MEC-PFC regions during spatial working memory tasks, which will help us understand the neural representation in each region and the interregional communication during successful memory access.

2. Examining the HPC (-EC) dysfunction and onset of abnormal neural oscillations in HPC-EC regions during young adolescence to adult periods focusing on the early phase of ScZ onset.

3. Determining the neural mechanisms responsible for updating acquired memories in the HPC-EC network during spatial navigation.

4. Investigating the initial stages of neural communication failures in the HPC-EC network using AD model animals.

ScZ Reverse-Translation Mice Showed Age-Dependent Hyper-Synchronous Events in HPC

(Molecular Psychiatry, 2024)

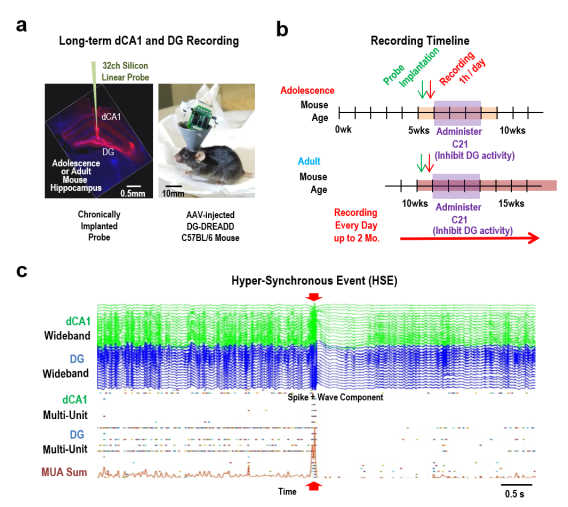

The study aims to understand how certain changes in the hippocampus, a brain region crucial for memory and learning, might be linked to schizophrenia (ScZ). We used a mouse model to mimic a specific dysfunction observed in human schizophrenia patients—reduced activity in a part of the hippocampus called the dentate gyrus (DG). When this region was inhibited during adolescence, the mice exhibited signs of hippocampal hyperactivity and behaviors resembling psychosis, such as social and memory impairments. However, the same inhibition in adult mice did not produce these effects, suggesting a sensitive developmental period during adolescence for the emergence of schizophrenia-like symptoms. The research highlights the importance of early brain development and how disruptions during adolescence may contribute to psychosis-related disorders like schizophrenia (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Reverse-Translated ScZ Mouse Developed Hyper-Synchronous Events during Adolescence DG Inhibition.

(a) Representative images of a coronal histology and a mouse post-surgery,

(b) Timeline detailing the sequence of probe implantation, initial baseline recording, and the subsequent continuous daily recording schedule, encompassing both adolescence and adulthood in mice.

(c) Illustration of an abnormal hyper-synchronous event (HSE), marked by red arrowheads, and its progression over time. These events mostly occur when the subjects are sitting quietly or sleeping.

Featured on the BBRF/NARSAD website

Featured on the BBRF/NARSAD website PI's Previous Studies:

Discovery of Gamma Synchrony during Successful Memory Retrieval (Yamamoto et al, Cell, 2014)

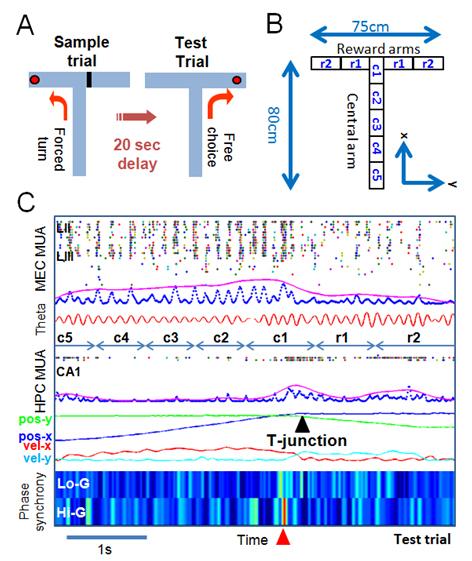

Neural Oscillation and Synchronous Activity in HPC-EC Network: Network oscillations are proposed to underlie the temporal binding of spatially distributed neuronal populations to enable information processing for cognition and its ensuing behavior. In addition, certain oscillations are hypothesized to allow conscious perception and awareness of associations between external cues and internal goals encoded in the synchronized brain areas. In particular, gamma oscillations correlate with perception, memory, and attention. Emerging empirical evidence suggests that gamma band oscillation (30-100Hz) power increases during working memory tasks in both humans and rodents, and other mammals as well. We found that increased oscillatory phase coherency and/or synchrony of gamma band oscillations within HPC - EC circuits plays a crucial role in successfully processing the working memory function. We discovered that the gamma phase synchrony at the T-junction of a spatial working memory task is tightly coupled with animal’s successful working memory execution during active running state (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Gamma Phase Synchrony in HPC-EC Network during DNMP T-Maze Task (A) A delayed Non-Match to Place (DNMP) task. (B) Spatial segmentation for detailed analysis. (C) An example of a success case run and gamma phase synchrony between HPC-EC network. Statistically significant gamma phase synchrony indicated by a red arrow.

Discovery of Reverberating Cortico - hippocampal Ripple Burst (Yamamoto and Tonegawa, Neuron, 2017)

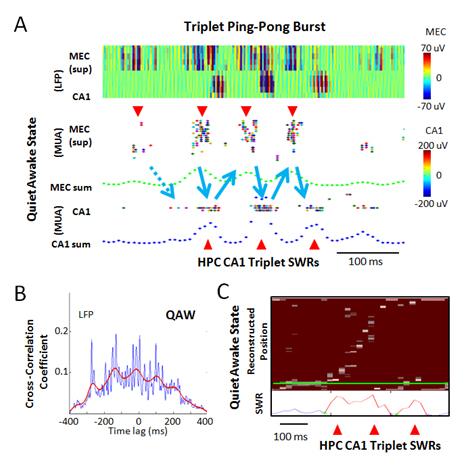

Another prominent hippocampal neural activity is the sharp-wave ripple associated memory replay of place cells during off-line state. the firing sequences of place cells during running behavior are re-expressed at an accelerated rate during quiet awake pauses in locomotion or during subsequent slow-wave sleep. This “replay” of place cells co-occurs with short-lasting (50~100 ms), high-frequency oscillations (100~200 Hz) called sharp-wave ripples or ripples in the local field potential (LFP). These sharp-wave ripple associated replays have been reported during slow-wave sleep or non-REM sleep, and quiet awake. The replay of hippocampal activity patterns has also been reported in relation to memory tasks. When the linear track explored by an animal is relatively short (around 1 meter), the firing sequence of a set of place cells covering the entire track can be replayed within a single ripple event of 50-100 ms. However, for a longer track, the replay of an extended place cell sequence of the track during the quiet awake state spans multiple ripple events which are called ripple-bursts that span 200~500 ms. We previously discovered that MEC layer III input to CA1 is crucial for concatenating short range SWR associated replay events into long-range SWR burst associated replay episodes (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Quiet Awake State Specific Ripple Burst Associated Alternating Burst Activities in MEC-CA1 Network. (A) An example of triplet sharp-wave ripple. Top panel: color-coded ripple band LFPs of superficial MEC and dorsal CA1 cell layer. Middle panel: Associated superficial MEC MUA with elevated burst activities (red downward arrow heads). Green dotted trace is smoothed sum of MEC MUA. Bottom panel: Detected CA1 MUA and its smoothed sum (blue dotted traces) with elevated ripple activities (a red upward arrow head). (B) Cross-correlation between MEC and CA1 using ripple-band LFP peak power times during QAW. Blue trace: 10 ms bin. Red trace: smoothed trend line. (C) An example of triplet SWR associated long-range replay by Bayesian decoding in CA1.

Development of Semi-Automatic Motorized Microdrive Array for Freely Behaving Rodent. (Yamamoto and Wilson, J. NeuroPhys, 2008)

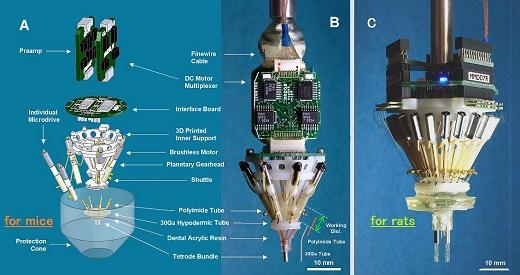

Large-scale multiple single-unit recording has been one of the most powerful in vivo electro-physiological techniques for investigating neural circuits. The demand has been increasing for small and lightweight chronic recording devices that allow fine adjustments to be made over large numbers of electrodes across multiple brain regions. To achieve this, we developed precision motorized microdrive arrays that use a novel motor multiplexing headstage to dramatically reduce wiring while preserving precision of the microdrive control. Versions of the microdrive array were chronically implanted on both rats (21 microdrives) and mice (7 microdrives) and relatively long term recordings were taken.

Figure 4: (A) An exploded view of the mouse microdrive array: Basically, the overall structure is identical to the rat version except for the scale and the additional interface board. This way of connection is to reduce overall weight while the animal is in the home cage. (B) An actual view of the mouse microdrive array: The bottom cannula has intentionally made angled tip to the right. In addition, the red-colored tubings are polyimide 30Ga tubes for the testing. The working distance and the relative length of 30Ga tube and polyimide tube are shown in this panel as well. (C) An actual view of the rat microdrive array: A twenty-one microdrive array version.