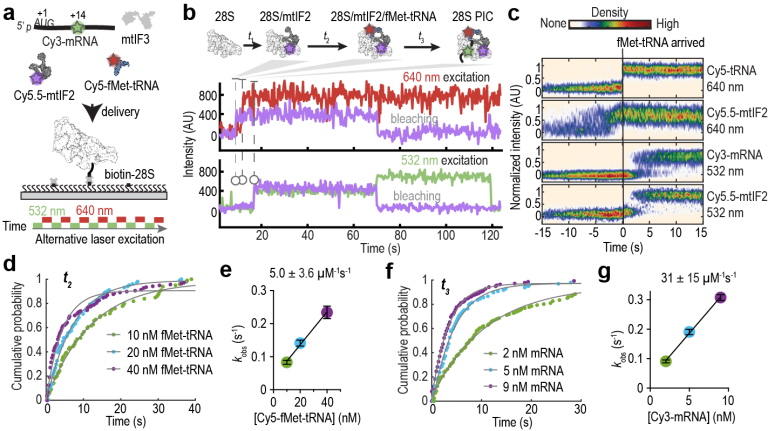

Single-molecule assay for observing mRNA–28S subunit binding.

(A) Schematic of assay to track Cy3-mRNA binding to tethered 28S subunits. (B) Example fluorescence trace of showing stable binding of mRNA (Cy3, green) to the 28S subunit. (C) Example fluorescence trace of mRNA sampling to the 28S subunit. (D) Mean normalized number of Cy3 molecules observed per field of view (FOV) in reactions under varying conditions. Indicated errors are standard error of the mean from three biological replicates with points representing the value from individual replicates. (E-G) Stacks of single-molecule traces from different reaction conditions, sorted by the arrival of the first Cy3 binding event. Each row represents a single 28S complex. Cy3-mRNA binding events are display in blue (≥ 30 s) or pink (< 30 s). N indicates number of analyzed molecules.

Choreography of human mitochondrial leaderless mRNA translation initiation.

Shen S, Xu Y, Kober DL, Wang J.

bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2025 Jul 10:2025.07.10.662049. doi: 10.1101/2025.07.10.662049.

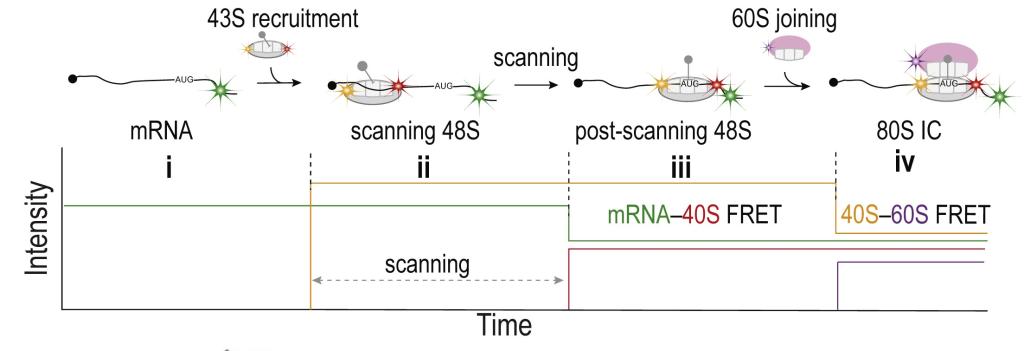

Real-time detection of initiation on single mRNAs. (A) Schematic (protein factors omitted) of the molecular events in early initiation. (B) Single-molecule assay setup. Capped-mRNAs were tethered in ZMWs, and fluorescently labeled ribosomes and elongator TC were added along with factors to start the reaction. (C) Schematic and (D) example trace showing 43S PIC (Cy3, green; direct illumination) binding to mRNA, 60S joining (Cy5, red; FRET with Cy3), and the acceptance of the first elongator tRNA (Cy3.5, yellow; direct illumination) by the 80S. The estimated mean times for 60S joining post 43S recruitment (tii+iii) and subsequent Phe-TC binding (tiv) from experiments described in (E) are shown above the trace. (E) Cumulative probability distributions of the observed 43S recruitment times when the mRNA was preincubated with eIF4 protein, Ded1p and Pab1p at different eIF4A concentrations. From top to bottom, number of molecules analyzed (n) = 152, 308, and 100. See also Figures S1, S2, and Source Data.

Rapid 40S scanning and its regulation by mRNA structure during eukaryotic translation initiation.

Wang J, Shin BS, Alvarado C, Kim JR, Bohlen J, Dever TE, Puglisi JD.

Cell 2022, 185, 4474-4487.e17.

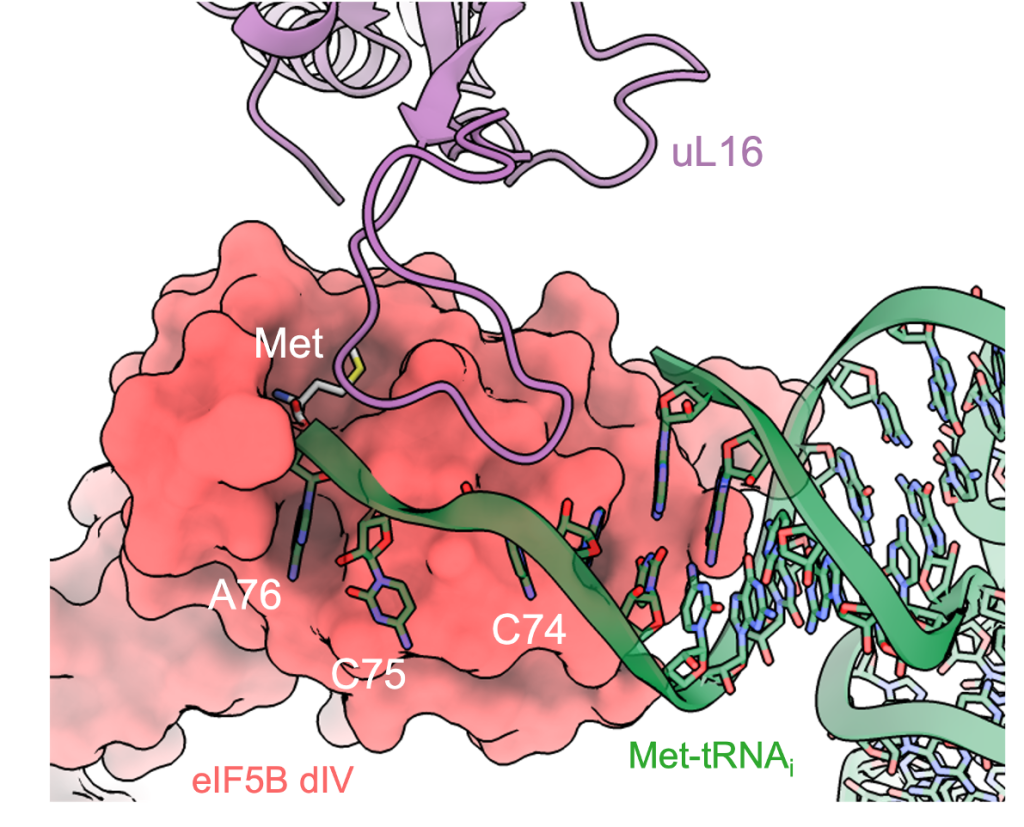

Ribosomal protein uL16 collaborates with eIF5B DIV in Met-tRNAiMet A76-Met recognition. a Overall view of the 80S/Met-tRNAiMet/eIF5B complex in an orientation centered on eIF5B DIV. b A detailed view of the Met-tRNAiMet conformation adopted while simultaneously interacts with the mRNA and eIF5B DIV on the 80S. c A detailed view of eIF5B DIV focused on the acceptor stem region of Met-tRNAiMet. DIV of eIF5B is shown in red as semi-transparent Van der Waals surface, Met-tRNAiMet nucleotides depicted in green with experimental cryo-EM density shown and uL16 residues are in blue with experimental cryo-EM density shown. d DIV of eIF5B and residues 102–110 of uL16 form a hydrophobic cavity where the methionine residue of Met-tRNAiMet is hosted.

Wang J, Wang J, Shin BS, Kim JR, Dever TE, Puglisi JD. Fernández IS,

Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5003.

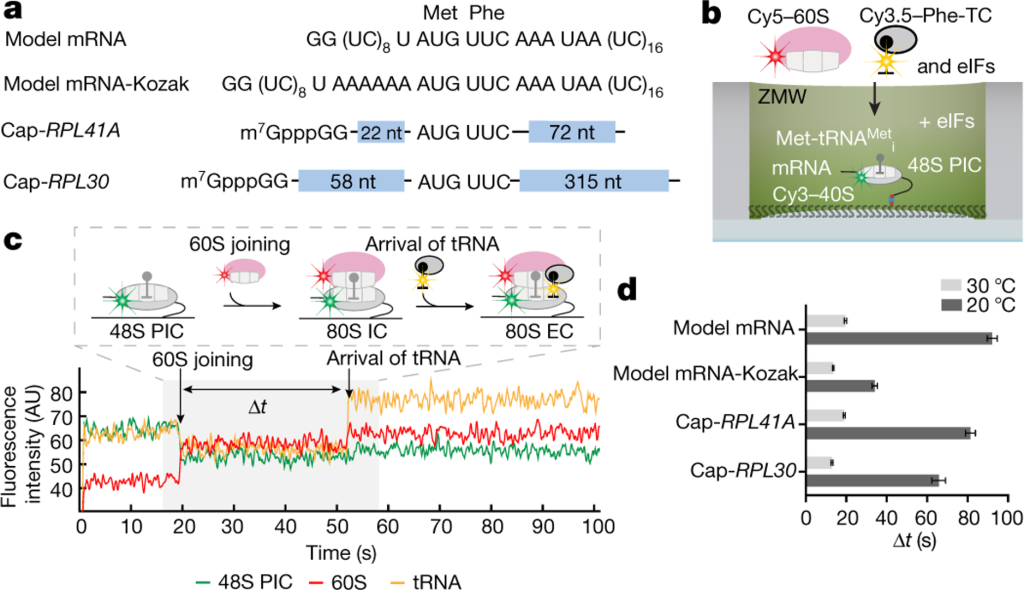

Real-time observation of eukaryotic translation initiation and the transition to elongation. a, mRNA constructs used in single-molecule assays (also see Extended Data Fig. 5d). All the mRNAs contain a UUC phenylalanine (Phe) codon after the AUG start codon and are biotinylated at their 3’ ends. b, Experimental setup for single-molecule assays. 48S preinitiation complexes (PICs) containing Cy3–40S, Met-tRNAi, and the 3’-biotyinlated mRNA of interest were immobilized in ZMWs in the presence of required eIFs. Experiments were started by illuminating ZMWs with a green laser and delivering Cy5–60S, Cy3.5-Phe-tRNAPhe:eEF1A:GTP ternary complex (TC) and eIFs. c, Example experimental trace (bottom) and schematic illustration (top) of the molecular events along the reaction coordinate. The dwell times between the 60S joining and the A-site Phe-TC arrival were measured for n = 118, 130, 130, 121, 189, 159, 164 and 136 molecules (d, from bottom to top for each bar), and fit to single-exponential distributions to estimate the average time, “Δt” (with 95% confidence interval), of the transition from initiation to elongation.

eIF5B gates the transition from translation initiation to elongation.

Wang J, Johnson AG, Lapointe CP, Choi J, Prabhakar A, Chen DH, Petrov AN, Puglisi JD.

Nature 2019, 573, 605-608.

Full publication list (# equal contribution)

24. Choreography of human mitochondrial leaderless mRNA translation initiation. Shen S, Xu Y, Kober DL, Wang J. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2025 Jul 10:2025.07.10.662049. doi: 10.1101/2025.07.10.662049.

23. Real-time detection of human telomerase DNA synthesis by multiplexed single-molecule FRET. Hentschel J, Badstübner M, Choi J, Bagshaw CR, Lapointe CP, Wang J, Jansson LI, Puglisi JD, Stone MD. Biophys. J. 2023, 122, 3447-3457.

22. Dynamics of release factor recycling during translation termination in bacteria. Prabhakar A, Pavlov MY, Zhang J, Indrisiunaite G, Wang J, Lawson MR, Ehrenberg M, Puglisi JD. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 5774-5790.

21. Rapid 40S scanning and its regulation by mRNA structure during eukaryotic translation initiation. Wang J, Shin BS, Alvarado C, Kim JR, Bohlen J, Dever TE, Puglisi JD. Cell 2022, 185, 4474-4487.e17.

20. eIF5B and eIF1A reorient initiator tRNA to allow ribosomal subunit joining. Lapointe CP, Grosely R, Sokabe M, Alvarado C, Wang J, Montabana E, Villa N, Shin BS, Dever TE, Fraser CS, Fernández IS, Puglisi JD. Nature 2022, 607, 185-190.

19. Plasticity and conditional essentiality of modification enzymes for domain V of Escherichia coli 23S ribosomal RNA. Liljeruhm J, Leppik M, Bao L, Truu T, Calvo-Noriega M, Freyer NS, Liiv A, Wang J, Blanco RC, Ero R, Remme J, Forster AC. RNA 2022, 28, 796-807.

18. Mechanisms that ensure speed and fidelity in eukaryotic translation termination. Lawson MR, Lessen LN, Wang J, Prabhakar A, Corsepius NC, Green R, Puglisi JD, Science 2021, 373, 876-882.

17. Dynamic competition between SARS-CoV-2 NSP1 and mRNA on the human ribosome inhibits translation initiation. Lapointe CP, Grosely R, Johnson AG, Wang J, Fernández IS, Puglisi JD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2017715118.

16. Structural basis for the transition from translation initiation to elongation by an 80S-eIF5B complex. Wang J, Wang J, Shin BS, Kim JR, Dever TE, Puglisi JD. Fernández IS, Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5003.

15. Dynamics of the context-specific translation arrest by chloramphenicol and linezolid. Choi J, Marks J, Zhang J, Chen DH, Wang J, Vázquez-Laslop N, Mankin AS, Puglisi JD. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16, 310-317.

14. eIF5B gates the transition from translation initiation to elongation. Wang J, Johnson AG, Lapointe CP, Choi J, Prabhakar A, Chen DH, Petrov AN, Puglisi JD. Nature 2019, 573, 605-608.

13. RACK1 on and off the ribosome. Johnson AG, Lapointe CP, Wang J, Corsepius NC, Choi J, Fuchs G, Puglisi JD. RNA 2019, 25, 881-895.

12. Kinetics of d-Amino Acid Incorporation in Translation. Liljeruhm J#, Wang J#, Kwiatkowski M, Sabari S, Forster AC. ACS Chem. Biol. 2019, 14, 204-213.

11. Ribosomal incorporation of unnatural amino acids: lessons and improvements from fast kinetics studies. Wang J, Forster AC. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2018, 46, 180-187.

10. How Messenger RNA and Nascent Chain Sequences Regulate Translation Elongation. Choi J, Grosely R, Prabhakar A, Lapointe CP, Wang J, Puglisi JD. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2018, 87, 421-449.

9. 2'-O-methylation in mRNA disrupts tRNA decoding during translation elongation. Choi J, Indrisiunaite G, DeMirci H, Ieong KW, Wang J, Petrov A, Prabhakar A, Rechavi G, Dominissini D, He C, Ehrenberg M, Puglisi JD. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2018, 25, 208-216.

8. De novo design and synthesis of a 30-cistron translation-factor module. Shepherd TR, Du L, Liljeruhm J, Samudyata, Wang J, Sjödin MOD, Wetterhall M, Yomo T, Forster AC. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 10895-10905.

7. Translational roles of the C75 2'OH in an in vitro tRNA transcript at the ribosomal A, P and E sites. Wang J, Forster AC. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6709.

6. Dynamic basis of fidelity and speed in translation: Coordinated multistep mechanisms of elongation and termination. Prabhakar A, Choi J, Wang J, Petrov A, Puglisi JD. Protein Sci. 2017, 26, 1352-1362.

5. Ribosomal Peptide Syntheses from Activated Substrates Reveal Rate Limitation by an Unexpected Step at the Peptidyl Site. Wang J#, Kwiatkowski M#, Forster AC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 15587-15595.

4. Kinetics of tRNA(Pyl) -mediated amber suppression in E. coli translation reveals unexpected limiting steps and competing reactions. Wang J, Kwiatkowski M, Forster AC. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2016, 113, 1552-1559.

3. Kinetics of Ribosome-Catalyzed Polymerization Using Artificial Aminoacyl-tRNA Substrates Clarifies Inefficiencies and Improvements. Wang J, Kwiatkowski M, Forster AC. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 2187-2192.

2. Facile synthesis of N-acyl-aminoacyl-pCpA for preparation of mis-charged fully ribo tRNA. Kwiatkowski M, Wang J, Forster AC. Bioconjug. Chem. 2014, 25, 2086-2091.

1. Peptide formation by N-methyl amino acids in translation is hastened by higher pH and tRNA(Pro). Wang J, Kwiatkowski M, Pavlov MY, Ehrenberg M, Forster AC. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014, 9, 1303-1311.