How do cells organize their metabolism and maintain lipid and organelle homeostasis?

To survive in a constantly changing environment, cells must sense nutrient levels and orchestrate metabolic remodeling to respond to changes in nutrient availability. How cells coordinate an organized response to stresses such as starvation or lipotoxicity remains poorly understood.

Our lab is interested in how cells spatially organize to adapt to a constantly changing world. To study this, we are focused on three main questions:

1) How do cells organize metabolism within organelles and sub-organelle regions to sense and adapt to stresses? (for more, see our recent proximity proteomics work (Merta, Cell Reports, 2025) or work studying spatial compartmentalization of lipid metabolism (Rogers, ELife, 2021; Wood, Cell Reports, 2020; Ugrankar-Banerjee, ELife, 2023), highlight of Rogers, et al. in ELife here.

2) How do cells store excess lipids in lipid droplets (LDs), and how are different types of LDs functionally specialized by cells? (for more, see our work on liquid-crystalline LDs (Rogers, JCB, 2022, see highlight here), our work on how proteins sense LD lipids (Speer, JCB, 2024) or our recent review (Henne and Cohen, Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2026).

3) How do organelles maintain lipid quality control (LQC) and suppress lipotoxicity from stresses such as lipid peroxidation? (for more, see our recent work identifying a new ER-localized lipid antioxidant enzyme APMAP (Paul, Developmental Cell, 2025).

Our lab also has a long-standing interest in lipid metabolism dysfunction in neurodegeneration. We have studied cerebellar ataxia SCAR20, caused by loss-of-function mutations in SNX14 (see recent papers including Datta, JCB, 2019 with highlight here; Ugrankar, Developmental Cell, 2019, see highlight in Science Signaling; and Datta, PNAS, 2020; reviewed here).

See below for additional discussion of our research:

The ER network is spatially organized and encodes lipid quality control (LQC) systems

The ER network is functionally and morphologically complicated, and exhibits protein compartmentalization as a mechanism for division-of-labor for ER functions. We have used proximity proteomics to understand how proteins are compartmentalized in the ER network. These studies have uncovered novel molecular tethers such as CLMN that provide ER-actin communication in cell motility (Merta, Cell Reports, 2025). Our work has also uncovered new LQC systems that protects ER function, such as APMAP, an ER-localized antioxidant that suppresses the accumulation of toxic oxidized lipids in the ER network (Paul, Developmental Cell, 2025).

Cells organize lipid metabolism at lipid droplet (LD) contact sites

Our lab is deeply interested in how lipid droplets (LDs) are spatially organized within cells. One mechanism for this is by attaching LDs to other cellular compartments and thereby compartmentalizing the LDs (and their high-energy lipid stores) in distinct sub-regions of the cell interior. LDs have long been known to become attached to other organelles like mitochondria, peroxisomes, and the ER, and we have studied metabolic cues and machinery that facilitates this (Henne, EMBO, 2018; Datta, JCB, 2019;Datta, PNAS, 2020). More recently we have dissected how LDs attach to organelles like yeast lysosomes (Hariri, EMBO reports, 2017; Hariri, JCB, 2019) and the Drosophila plasma membrane (PM) of adipocytes (Ugrankar, Dev Cell, 2019). We find that all these LD-organelle contact sites promote lipid exchange between the LDs and the attached organelle, which ultimately influences cellular energy and lipid homeostasis.

Inter-organelle contacts act as "metabolic platforms" for enzymes and fine-tune metabolic pathways

Early work on ER-mitochondrial contacts indicates that inter-organelle contacts are "hotspots" for lipid synthesis enzymes (Vance, JBC, 1990). Motivated by these pioneering observations, our lab has explored how inter-organelle contacts act as metabolic platforms for the organization of enzymes in metabolic pathways. We find that yeast nucleus-vacuole junctions (NVJs) are sites of enhanced mevalonate synthesis during glucose starvation. NVJ tether Nvj1 selectively recruits the HMG-CoA Reductases (HMGCRs) Hmg1 and Hmg2 to the NVJ. Using radio-pulse labeling, we find this HMGCR spatial partitioning enhances mevalonate pathway flux and promotes metabolic adaptation for yeast facing glucose restriction (Rogers, eLife, 2021).

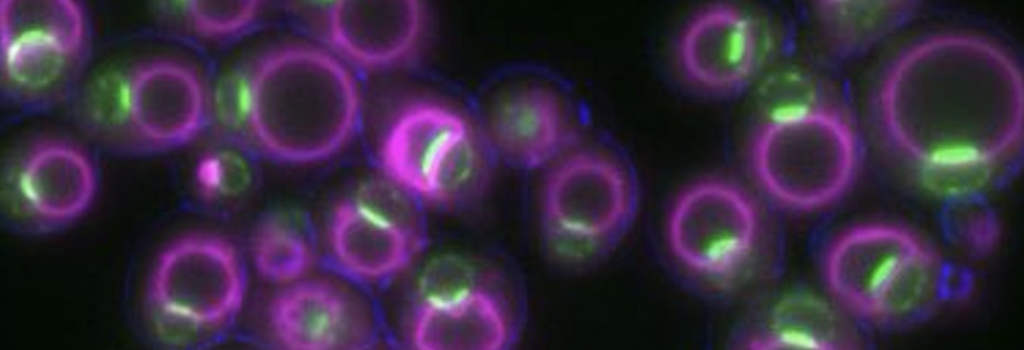

Lipids within lipid droplets exhibit phase transition properties

Our work on organelle organization has motivated us to understand how lipids within lipid droplets (LDs) are organized. Past studies have indicated that lipids such as sterol-esters can sometimes undergo phase transitions in LDs, giving rise to liquid-crystalline lattices within the LD interior (Mahamid, PNAS, 2019). The metabolic cues governing this have been unclear. We find that in yeast, glucose restriction can promote sterol-esters to transition into a liquid-crystalline lattice (LCL) phase (Rogers, JCB, 2021). The formation of LCL-LDs requires triglyceride lipolysis, which helps sterol-esters transition from a disordered to a liquid-crystalline phase. The harvesting of these triglycerides also promotes fatty acid oxidation in peroxisomes to help the yeast survive glucose restriction. We also find that LCL formation alters the LD proteome, causing some proteins to de-localize from LCL-LDs whereas others remain LD associated.

Organelle contacts influence cellular decision making

Finally, we have explored how inter-organelle contacts influence cellular decision-making. Partnering with Dr. N. Ezgi Wood, we discovered that yeast NVJ expansion is highly predictive of cellular behavior following glucose starvation (Wood, Cell Reports, 2020). Specifically, we find that yeast exposed to acute glucose removal becomes either quiescent or senescent. Yeast which expands their NVJs is much more likely to become quiescent and resume budding following glucose replenishment, whereas senescent yeast with small NVJs fails to resume growth even with glucose replenishment. Our work also points to numerous other metabolic factors that contribute to this cellular decision.